This text is segments from Introduction of the book, Act of State – A Photographed History of the Israeli Occupation. The book is based on a photographic exhibition on the history of the occupation that was mounted at the Minshar art gallery in Tel Aviv on the 40th anniversary of the Six-Day War. Curator of the exhibition, Israeli philosopher Ariella Azoulay, put together work of some 80 photographers, shows 700 black-and-white and color pictures. provides visual testimony of the texture of Israel’s occupation of Palestine establishing a forty-year narrative of the painful aesthetics of destruction.

The exhibition Act of State proposed to observe the citizenry of photography in its daily routine, the occupation’s building blocks.[1] Every day, for forty years, these people are ruled by a power that does not recognize them as citizens and rules them as subjects. Like the exhibition, the book, too, is an attempt to propose a civil point of view over a period of forty years of occupation. This is a point of view that refuses to see the photographed persons only as occupied or as mere objects of photographs. This point of view offers the space of photography as a space in which those who have been forced into statelessness, deprived of citizenship, comprise – the citizenry of photography. Through photography they demand their right to political speech and action and invite the spectators to reinstate with them the political space of which they have been dispossessed. The traces of their action are imbued in the various frames, and the spectators are invited to reconstruct it even when it seems negligible, nearly invisible.

Eldad Rafaelie, 1995. Bethlehem. Closure, a routine matter on every Israeli Independence Day. Palestinians are forbidden to enter Israel. But the sky is not excluded by edict. For a brief moment, the beauty of the fireworks removes from one’s mind the double context of this date which for the Jews signifies independence, while for Palestinians – their disaster (Naqba).

Through photography they demand their right to political speech and action and invite the spectators to reinstate with them the political space of which they have been dispossessed

The photographs are rich historical documents that enfold several – at times contradicting – narratives, of all who took part in producing that which the photograph shows. At one and the same time they show the narrative of the occupier and that of the occupied. I shall illustrate this with a photograph by Avi Simchoni (Israel Sun Agency) of 1969.

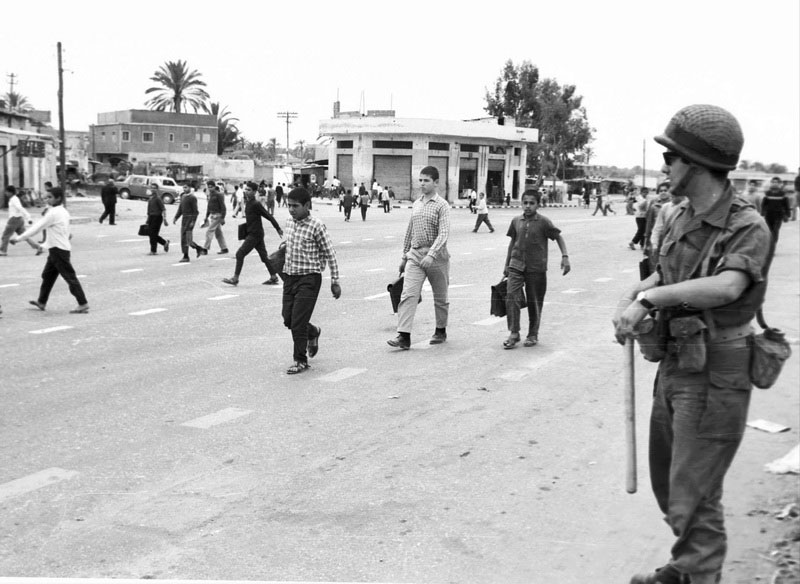

The foreground shows an arrest of a Palestinian by two soldiers. Deeper into the frame, to the right of the arrested person, one might detect another soldier, vigorously waving a club in the air. The gaze that follows the direction in which the club is raised finds several dozen Palestinian youngsters being chased back into their village. The army does not chase them away in order to spare them the sight of an arrest – they have seen many such arrests and will be seeing many more. The army chases them away in order to prevent them from congregating, from turning into civilian spectators whose point of view might disturb the coherence and justification with which the army wishes to don its actions. Their removal from the scene/frame, from the event that could have been at the center of the frame, was a matter of course, a part of the persistent and ongoing attempt to prevent the creation of a political public space in which the Palestinians could assemble freely and begin to discuss whatever they saw or consider how to react to the goings-on.

Alex Levac,1991. Nablus. No rifle-cleaning flannel strips left, so one of the detainees is simply ordered to take off his shirt and use it as a substitute blindfold. The soldier leading the line smiles at the camera like a principal dancer on stage, setting pace for his troupe. Not only are the Palestinians blindfolded and disoriented, they have been instructed to hold hands and move in line so the soldier can easily control their movement as he leads them to court.

***

It is wrong to see the First Intifada as the birth of Palestinian resistance, but the Intifada was, no doubt, a turning point as regards the visibility of the Occupation.

Only when it broke out, did harsh everyday reality in the Occupied Territories – clearly apparent in the photographs brought here – begin to appear as sheer horror; the stupid smile spread over the soldier’s face as he holds his gun like a proud warrior defending his homeland, while behind him ten Palestinian men wither on the ground for no apparent reason and who knows for how long, begins to be seen as an event, something to be reported. In this sense, the First Intifada was a radical turning point in that it managed to dislodge the homogeneity which the occupier had imposed upon the Israeli field of vision, and crack it, creating a place and giving presence to the subjugated Palestinians’ point of view.

***

The book insists on reconstructing what the picture shows, and exposing it as a complex field of relations. This insistence is based on the assumption that under Occupation, the space of photography is not just evidence of the acts and goings-on of humans, but often the arena in which they act, especially when they are denied proper civil existence.[2] In many of the photographs, the photographed persons take an active part in the photographic act and see it, like the photographer facing them, as an alternative framework, even if shaky, for the institutional frameworks that abandon them, injure them, shirk responsibility and refuse to make amends for the damages they do. The naturalization of the photographed persons through the act of photography itself assumes the existence of a civil space in which photographers, photographed and spectators share the recognition that what they see is unbearable, superfluous, an Act of State that should be defied.

Nella Magen Cassouto, 1967. The Wailing Wall. The plaza is already marked by various types of separation fences. The people who come to pray at the site are crowded against the Wall. From the center of the plaza, cleared of the demolition rubble that was the Maghrabia Quarter, a sign in three languages (Hebrew, English and French) warns: “Photography forbidden on the Sabbath”. Perhaps out of consideration, the sign does not include the indigenous language of those who – until several days earlier – lived here. In the foreground, the rubble of the Maghrabia Quarter.

The civil space of relations enabled by the photograph is a space in which the plaint of the photographed person can be heard and overcome the limits and limitations imposed by a sovereign rule that has imposed itself upon millions of non-citizens. The Occupation is a national project towards which this ruling power mobilizes its citizens from very early on. Immensely potent ideological mechanisms wish to diminish citizenship and identify it with participation in this national project. In this situation, the use of photography – by the photographed, the photographers and the spectators – is a means of resuscitating common citizenship in both senses: citizenship as a basis for solidarity relations between the governed of various ethnicities vis-à-vis the regime and the evil it produces; citizenship as a buffer between citizens and the regime that demands their mobilization and support of its projects, contrary to the interests of all governed (both citizens and non-citizens).

In many of the photographs, the photographed persons take an active part in the photographic act and see it, like the photographer facing them, as an alternative framework, even if shaky, for the institutional frameworks that abandon them, injure them, shirk responsibility and refuse to make amends for the damages they do

The insistence on differentiation and nuance characterizing the shown photographs is part of an objection to the discourse that claims that “the viewers’ eyes have dulled with time”. An effort is made here to avoid the dominant norm: “If we’ve seen one picture of the Occupation – we’ve seen them all”. The singularity of what people undergo is not given, not even in photographs that make things visible as it were.

Ariela Shavid, 1968. Gaza. The soldiers and tourists look to the left, towards something going on outside the frame and hidden from its viewers. The only thing obvious to the viewer is the fact that the two Palestinian boys appearing in the frame turn their backs to that same occurrence and attempt to get away stealthily. They do not seem interested or are not allowed to watch it. Is a mass arrest taking place there, or perhaps a forbidden political gathering?

To enable its appearance, the photograph must be made to speak. Responsibility must be taken for the photographed persons who – present there in the center or margins of the frame – direct themselves at the viewers, demand in their gaze to reinstate that solidarity of the governed. We were aided by few testimonies of the persons photographed (the few that were available, especially regarding the recent two decades), direct information about specific photographs that prevents their being turned into an illustration of a generalized theme (place of publication, year, context), indirect information (reports of the phenomenon they represent, and period descriptions) about them, cross checking with other photographs taken at that same situation or another, delving into every detail in the photograph while reenacting the photographer’s location, cooperation and involvement of the photographed, and circumstances of the photograph (stealth or license, prey or loot) and through conversations with the photographers.

In spite of the similarity between certain photographs, any photograph selected enabled us to see something that appears only in it and nowhere else. These singular moments may belong to different planes of the photograph. At times, when those singular moments are present on the visible plane, they should be pointed at in order to be seen. Such, for example, is a photograph from 1967, where a crowd of Jewish Israelis are seen gazing up at the Wailing Wall. Directing the viewers’ attention to the pile of debris at the bottom part of the frame enables the presence-ing – in such a hegemonic photograph – of the Maghariba quarter that had just been demolished to make room for the Wailing Wall to appear the monument it is. At times, such a moment belongs to the space relations of the photographic event, and emerges only if we assume that the persons photographed actively participated in the act of photography and did not just let someone take their picture. Such an instance is the photograph of Zacharia Zbeide, the ‘wanted man’ who, at the moment his photograph is taken, knows that the security forces are out to hunt him down and chooses (in 2001) to face a photographer (Miki Kratsman) for a classical portrait in which he seems to be saying: “Here I am”. At other times, the singular moment does not even exist visually – it is present in the background of the photograph, in its unseen context, lending the situation a more tangible experience. A case in point is the knowledge that the woman photographed has been granted ten minutes to gather her belongings before the bulldozer begins to raze her home (Yosef Ohman documented the demolition of Imwas village, 1967 or Nir Kafri four decades later).

In exhibition venues, photographs are usually captioned laconically. The extreme case is the common “Untitled”. The accepted norm is a nondescript mention of the year and place. This marking convention expresses an age-old separation of image and text, particularly in the art world and the media, and in culture in general. The result of this form of display is that spectators very rarely receive any information about what they see. But this information is crucial to understanding what the photograph shows. It is important, for instance, to know what enabled the photographer’s presence at the scene: was he or she there as a soldier (Oded Yedaya conducting house searches during the First Intifada in1989; Simcha Shirman while making arrests, 1988) or as a press photographer (Uzi Keren, Jim Hollander, Israel Sun or Miki Kratsman). Is he authorized to be there (Ziv Koren present at the arrest of suspects, 2006, or Nir Kafri prior to demolishing houses, 2002) or sneaking into the scene (Rina Castelnuovo in front of the Dome of the Rock, 1998, or Eldad Rafaeli during curfew, 2002). Was he or she commissioned by the army (photographing the terrorist lying on the ground, shot, in Israeli army uniform, photographer anonymous, 2002), or present independently of the army (Ariela Shavid, Nella Magen Cassouto, Tzachi Ostrovsky, Joel Kantor or Alex Levac). Such knowledge expands the field of vision provided by the photograph, extricating it from its pictorial state and turning it into a live theater of human relations.

Yosef Ohman, 1967. Imwas. A weary reservist in full gear explains to the woman in the picture that within minutes she will have to leave her home. Does she know she will never return? Does she know that nothing of it will remain? Does he know what he is doing? Is the young soldier on the right covering his eyes with his fingers because he has trouble dealing with the horror of which he is a part, or is this, perhaps, an expression of his impatience with the woman who is trying to win time and appeal to the reservist’s feelings?

Similarly, it is no less important to know the particulars of the photographed persons’ involvement: were they willing subjects, or did they freeze at the sight of the camera because the photographer was, perhaps, in uniform, perhaps armed, perceived as ordering them “to be photographed”? (Oded Yedaya during house searches in Gaza, 1989). Were the snowballs in the hands of the masked Palestinian boys (Nir Kafri, 2002) being thrown at their mates or at soldiers they encountered? Does the officer who prevents his men from continuing to kick the shackled Palestinian lying at their feet do so because of the photographer’s arrival at the scene? (Miki Kratsman, 1988) It is also important to know that the narrow bathroom, where a mother and her children are seated under the sink, is the only room that survived the demolition of their home (Micha Kirshner, 1988); that the child facing the camera who raises his hands in a proud V gesture was hit in his head by a live bullet (Anat Saragusti, 1983); that the officer walking away from a group of boys waving behind him has left in agreement (Jim Hollander, 1987); that the Palestinians bathing in the sea gathered there in masses minutes after the last Israeli army trucks and tanks left Gaza (Nir Kafri, 2005); that the lifeguard shack on the Gaza beach was once an Israeli army post (Guy Raz, 1999); and that the war machine in the picture both kills people and demolishes houses (Meir Wigoder, 2005); that the armored vehicle driving through the town is calling upon its residents to come out of their homes (Government Press Office, 1967); that the bus in which Palestinians’ IDs are being checked is actually in Tel Aviv (Tzachi Ostrovsky, 1968); that the scene watched by Palestinians is the Four Days March about to end in Jerusalem (Israel Sun, 1969); that the fireworks display mesmerizing the Palestinian crowd overhead is actually held in celebration of Israel’s Independence Day (Eldad Rafaelie, 1995). This information equips the spectators with the necessary minimum (never sufficient) to understand the situation so that they can revert to the photograph and read it anew.

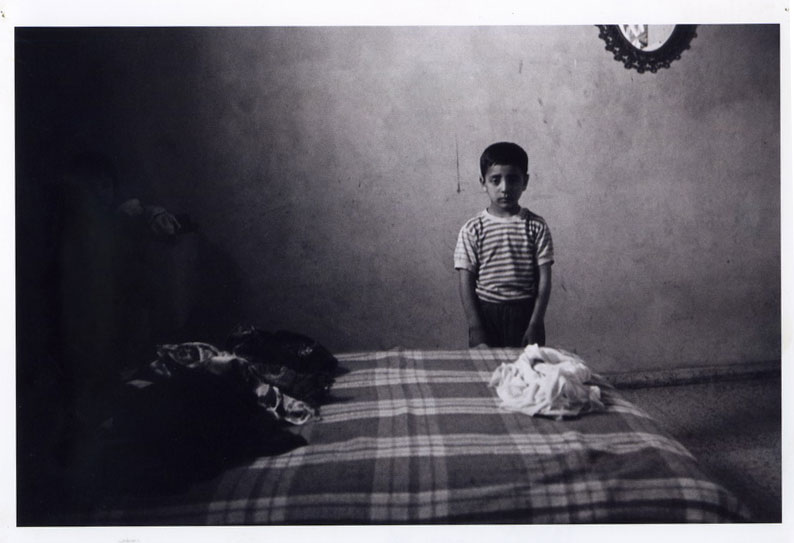

Oded Yedaya, 1989. Gaza. House searches in the middle of the night. The additional child on the left, absorbed in the dark, stands behind the bed, his hands lowered and his gaze to the camera. When the photographer facing them broke into their home in uniform in the middle of the night, did they have any other way of understanding his armed presence except as an order to stand still, braced and ready for the next command?

***

When I started working on this exhibition, I realized there is no existing photographed history of the Occupation which I might use as a point of departure, argue with – and deviate from it. I never imagined how complicated it would be, producing such a body of information, and did not comprehend the implications of the fact that no public institution collects and preserves in any orderly fashion photographs of the Occupation which might be studied and reveal its history. Daily press archives contain numerous photographs, but the rights to use them are not owned by the newspapers themselves. The fact that a newspaper – one of the main gatherers of information about the present – is not a source to be cited for non-commercial purposes with the visual information it presents every day to an enormous reading public, begs the question: is historical research conceivable in which researchers are forbidden to cite stories of journalists because these are the owners of their articles? Does the press not bear an ongoing responsibility for the information – visual material included – that it presents its readers, a responsibility that obliges it to change the form of its contract with the photographers, even if resulting in higher costs, in order to be able to eventually cite their photographs at least non-commercially in the same manner as newspaper texts? The immediate meaning of the present state of affairs is that visual information distributed by the press is one-time material that may not be put to public use. Photographic property relations were institutionalized, warped, as an outcome of historical circumstance, as though photography were simply a work of art, and as a result, persons photographed as well as interested (non-commercial) viewers have, in fact, no right to fully participate in the public discussion of the photograph itself.

Still, the fact that Palestinian photographers’ presence in the exhibition is diminished, does not make it an Israeli exhibition. My working assumption regarding photography challenges essential distinctions between a Jewish-Israeli point of view and a Palestinian one

Under such circumstances, this book and the exhibition on which it is based were not possible to create without the generosity of dozens of photographers who opened their archives to me and gave me their works. Without the photographers’ archives, the only way to research and present the history of the Occupation from the perspective of photography would depend solely on photographs preserved by government agencies that open to the public at large only a part of their photographic material, such as the Government Press Office and the army spokesperson office. Those photographs are indeed important and some of them are included in the exhibition, but serious study cannot be based on these censored databases which ruling power collects and supplies. The veteran press-photography agencies active in Israel since the sixties are an important source as well, but these are private agencies and they usually charge money for even looking at their material, and considerably more so for presenting or reprinting their photographs.[3] Since the First Intifada, and especially the Second Intifada, massive public visual information has appeared through the presence of various organizations and associations active in the Occupied Territories, committed to resist the Occupation. Their activity includes a whole channel of photographic documentation and its preservation. Activists and researchers working for these organizations take photographs, collect and preserve them on a regular basis. Another change has taken place at the onset of the 21st century, with the proliferation of digital cameras and electronic dissemination of news. But the much greater accessibility of photographs for study has not altered the issue of reserved rights over photographs that are retained by the photographers.

Miki Kratsman , 2001. Jenin. Until his portrait was taken, Zachariah Zbeide was wanted by the security services, but his face was unfamiliar. Courtesy of the photographer, and his own exposure to the camera, he passed over this game of hide-and-seek with the GSS – that had remained clandestine, turning him into a “wanted” security outlaw – into the public sphere in which he wishes to appear now through a direct portrait, identified and defiant, as a freedom fighter against the Occupation and the “targeted executions” apparatus it had created.

The extreme escalation in oppressive measures taken by the Occupation regime during the past decade, alongside the growing number of Palestinian photographers boycotting and refusing to collaborate with Israel – even those who until a few years ago still took part in projects openly resisting the Occupation in cooperation with Israelis – have kept them from participating in this project and it is therefore based especially on the work of Israeli photographers. Still, the fact that Palestinian photographers’ presence in the exhibition is diminished, does not make it an Israeli exhibition. My working assumption regarding photography challenges essential distinctions between a Jewish-Israeli point of view and a Palestinian one. Firstly, a photograph is a result of an encounter between the photographer, the camera and the persons photographed, and the power relations among them are not necessarily stable, nor contracted into a dichotomy that has been established within a certain theoretical discourse between the photographer as subject and the person photographed as object. Secondly, that which has been drawn in the frame is never merely a reflection or expression of an ideological point of view that may have been the photographer’s, certainly not his or her national identity, since the photographs of situations such as represented in Act of State always contain, as well, the point of view of the persons photographed. Therefore, even if the hegemonic Jewish-Israeli gaze – coming into being during the war and in the euphoric period immediately following – was mostly indifferent to the harsh sights created by the Occupation, these sights did penetrate hegemonic frames. Thirdly, one cannot reduce the meaning of the photographic image to a mere ‘denotation’/instruction of the photograph (“This is x” or “that is y”); this meaning is established in a domain of relations that is opened and organized anew every time a viewer look at the photograph.

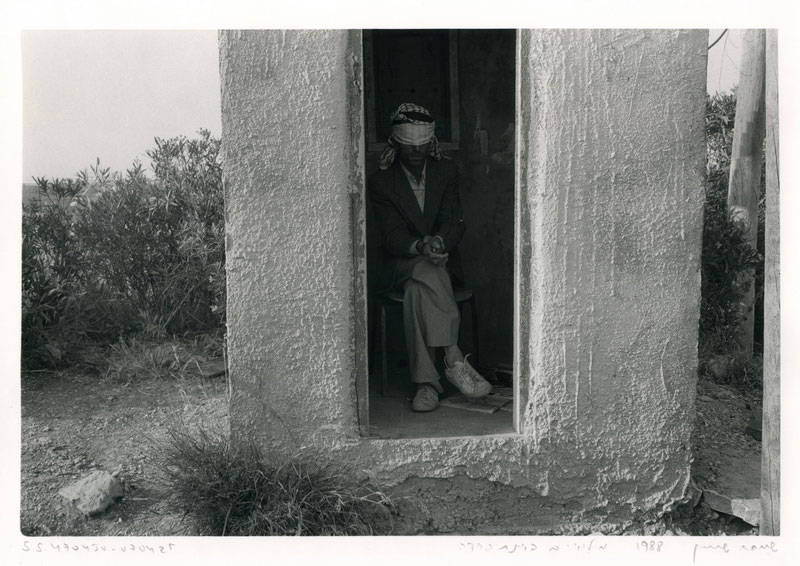

Simcha Shirman, 1988. Deir Amar. The phrase “He must be blindfolded” instructs the soldiers in their arrests. No one wonders about this automatic act that denies the Palestinians their eyesight. Seating the detainee on a chair in a secluded building is already an independent initiative on the part of these particular soldiers who preferred not to have his presence (albeit sightless) disturb them while pursuing their arrest mission.

Most of the photographs in the Acts of State project, then, are by Jewish-Israeli photographers who – immediately following the 1967 war – documented the demolition of Imwas and Beit Nuba villages and their refugees (Yosef Ohman), the demolition of the Maghariba neighborhood (Nella Magen Cassouto), the demolition of houses in Hebron after the war (Ariela Shavid), the refugee camps (Rachel Hirsch, Anat Saragusti, Israel Sun, Osnat Krasnansky, Shuka Glotman, Miki Kratsman), protest and resistance (Jim Hollander, Joseph Algazy, Alex Levac), the poor conditions of employment of Palestinians in Israel (Uzi Keren, Israel Sun and Joel Kantor), incursions into Palestinian homes (Nir Kafri, Anat Zakai, Noa Ben Shalom, Rina Castelnuovo, Dafna Kaplan), arrests of Palestinians and searches held in their homes and on their bodies (Miki Kratsman, Eldad Rafaelie or Ziv Koren), detention centers (Nir Kafri and Roi Kuper), military devices and facilities used by the army (Meir Wigoder and Guy Raz), direct body injury (Micha Kirshner and Ruchama Marton), Occupation “landscapes” (Israel Sun, Assaf Evron, Nella Magen Cassouto and Simcha Shirman), mobile POW pens (Tzachi Ostrovsky). They did this because they, or the newspaper they were working for, saw the goings-on at least in certain points in time as a moral or political outrage that must be recorded, and should become a matter of public concern.

Many of the photographs I assembled for the exhibition reached me with only partial information, if at all, usually including the year they were taken, the place and nature of the occurrence. However, that nature usually referred to the event where a photo was taken, and very seldom directly to the substance of that specific shot of that event. Thus, for example, the description “demonstration” or “arrest” accompanying a large part of the photographs was in fact wholly secondary to the highly complex goings-on I discovered in a lengthy observation of the photographed persons. I tried to imagine the situations documented in the photographs, to assume various details cut away from the rectangular frame, or such that could not be contained in it but are materially relevant to that which is seen. Where will she place her barefoot baby in order to change its diaper, as their domicile -until just a few hours ago – has turned into rubble and dust? What will she do when her child is hungry? Or when she gets tired? When she will need to get away from the bustle, from its crying, to have a moment to herself? Where will she cook her baby’s soup? Calm it down? How many houses were razed in order to produce this plaza? Was the photograph of the wanted person familiar before he decided to have his picture taken? Where do they direct their gaze? What are the sights they see when they come home from school every day, what kind of decisions are they called upon to make at such an early age? Why are these arrested while those are removed from the scene? Some of the questions might be answered, others remain unanswered, but merely posing them enables us to glean more and more details from the photograph and respond to the people photographed, whose constant presence demands us to act upon our minimal civil duty and political imagination and not to leave them in the vastness of horror where anything seen in them is etched in that low resolution that says “I can’t look at this” or “We can do nothing”.[4]

Avi Simchoni, 1969. Gaza. The distance kept among boys walking down the street with their schoolbags is not characteristic of children walking home from school. Their own experience and the presence of a soldier – a club in his right hand – are ample reminder to avoid walking in groups if they do not want to be suspected of political gathering.

The fact that most of the persons photographed are not identified by their name and were not allowed to reach Tel Aviv, where the exhibition was held, and could not view the photographs on display, has cast its shadow over the project from its very inception. The publication of this book is an opportunity to share this archive with the people photographed in it, whose pictures have forcedly become part of a political album shared with their occupier.

[1] On the citizenry of photography see (Ariella Azoulay, 2009. The Civil Contract of Photography, Zone Books).

[2] And still, unfortunately, I could not restore the proper names of most of the persons photographed in the pictures shown here.

[3] Two photography agencies opened their archives for us: Israel Sun and I.P.P.A. Assaf Shilo, owner of Israel Sun, even let us use an unlimited number of photographs.

[4] Francisco Goya, who attached various captions to the horrific images he painted, insisted on refuting the point made in the caption through the painting gesture whose essence is to show that which cannot be seen or at the sight of which one can do absolutely nothing. On a decisive moment that places Walker Evans and Margaret Bourke-White in counterpositions in a debate about photograph-caption relations see John Stomberg, “A genealogy of orthodox documentary”, in Mark Reinhardt, Edwards Holly, and Erina Duganne (eds.), Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain, The University of Chicago Press and Williams College Museum of Art, Chicago 2006.